“Suddenly the cloud the caught up with me. A dense, white fog swallowed up everything around me, an advancing front of claustrophobia taking no prisoners”

Sh*t.

That was my immediate thought as I momentarily paused my hasty decent to look back up the slope I had just scrambled down. I was performing the half run, half skid which anyone who has tried to descend a trail in pouring rain will know well.

Miniature rivers gushed around my feet as I tried to identify the stones that wouldn’t give way beneath me. Just a few metres above me, thick, white clouds were chasing me down the slope – and by my calculation, they would overtake me in a matter of minutes.

Just moments ago, I had been over two kilometres up in the sky, straddling the Slovenian-Austrian border. I had summited Mount Stol, the highest peak in the Karavank Range at over 2,200 metres. For a few minutes, I felt like I was the only person in the world, surrounded by nothing but rock, cloud and thin air.

But as I stood taking in the otherworldly views, my reward after hiking hours in the blistering heat, something in my skin tingled. It wasn’t just the awe-inspiring sea of peaks which lay before me. It was that sixth sense, that instinct possessed by any outdoors nut that it’s all about to go tits up if you don’t act fast, which was speaking to me.

And I was right. The moment I stepped down off the summit and began to descend the path leading down the exposed scree slope, clouds rolled in quicker than I have ever seen and a low cymbal crash of thunder echoed through the sky.

Alright, time to scram, I thought. Minutes later, the sky was alive with an orchestra of thunderclaps and lightning streaks, rain was pouring down and visibility was disappearing fast. And I was still a good couple of hours from the bottom.

This was not a possible situation I had presented to my university supervisor when going through the risk assessment for my undergraduate research project (and, if anyone asks, never happened). In fact, I wasn’t technically here to climb any mountains at all, but rather to research bees, wasps and other pollinators. I’m an ecology student, so when the opportunity came up to design our own year project, I thought what better way to combine some meaningful research with a mountain adventure?

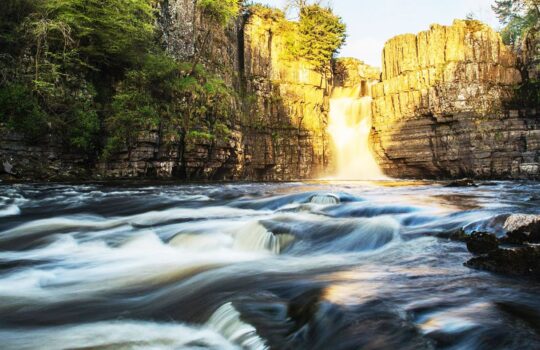

My hypothesis was simple, in theory: assess whether hydropower dams affect pollinator abundance along rivers. I’ll break this down, as I realise there is perhaps more than one foreign word in that sentence to most.

We have seen a building spree of hydropower dams across Europe, built to quench the thirst for energy that comes with a rapidly developing continent. Whilst many people see them as a source of pure, green energy, what are often forgotten are the environmental consequences which come with dividing up rivers and the ecosystems which depend on them.

There has been a recent flurry of smaller dam constructions, projects which you could definitely argue do not produce enough electricity for the ecological disturbance they cause. The aim of my research is not to pass judgement (I’ll leave that to the experts), but simply to investigate whether there is an effect on entomofauna (or insect life, to me and you), and pose that this needs to be taken into consideration when planning construction.

To my knowledge, nobody has looked at any effects of dams on pollinators. We know that the habitats surrounding rivers are high in biodiversity, thanks to the rich nutrient flow from the water.

Many studies have been done on the impacts on aquatic species under the water, and we know that disturbance from dam construction affects soil composition and plant life, too. So I wanted to take it one step further and see how pollinators were faring amidst all this; after all, with such a rapidly growing human population to feed, sufficient pollination of crops and other edible plants is an ever more pressing issue.

So having convinced my tutors that this was indeed an exciting, unique bit of research to be done, I was given the green light to head out to collect data. I wanted to head outside of the UK for my research; not only in an attempt to sate my curiosity to see more of the world but also since there is already a huge amount of biodiversity data from British studies.

After reading that Slovenia was one of Europe’s biodiversity hotspots and had recently declared the honeybee a national animal, this seemed like the perfect location to spend two weeks hiking up mountains and along riverbanks. I focused my research on the River Sava, the largest tributary of the Danube, whose upper reaches in northwest Slovenia were peppered with hydropower dams of varying sizes.

So began 15 days of mountains, rivers and bug counting. For each site I had chosen, I would hike for around two hours to the location, then take transects (walking 100m and counting whichever insects you see a metre either side of you) up and downstream of a dam to compare if the number of pollinators differed. This would take another couple of hours or so, then leaving me with the rest of the afternoon and evening to go and explore.

Of course, I had factored in a few extra days in case of bad weather (bees are famously not fans of wet weather). But I was mostly blessed with full sun, so I took the odd day out to do full day hikes and summit some of the higher peaks around me, as well as my daily, smaller evening hikes.

One of the best things about hiking in Slovenia is the trail infrastructure, mainly thanks to the country’s strong mountaineering culture which has been present for the last century or so. Mount Triglav, the country’s highest peak, is considered a right of passage for any Slovenian.

I discovered that most trails are extremely well marked, meaning you can spend less time with your nose in a map (most tourist places hand out the equivalent of OS maps for free) and more time absorbing your surroundings. For someone with an occasionally questionable sense of direction, not getting lost once in two weeks was quite something.

And the surroundings are breathtaking. For the most part of my stay, I was in a campsite near Jesenice, an industrial town just south of the Austrian border lying. The town lies in the valley of Lake Bled and is surrounded by a network of incredible granite peaks rising above the Sava River.

Slovenia boasts 60% forest cover, creating a nexus of habitats for wildlife to thrive. Since I was a silent solo hiker, almost every time I went out I would encounter deer, foxes, eagles or the odd marmot. I even had one young male deer try to rut with me – quite different to the fleeting glimpses of muntjacs we’re accustomed to in the UK!

But perhaps one of the most special natural phenomena I experienced took place every evening. Just as dusk began to set in and the sky was painted deep indigo, hundreds of fireflies would appear for about an hour. I remember after one particularly long day, I misjudged the distance back to camp and was trudging wearily back along the river when I looked up to see a swirling haze of tiny, green orbs twinkling all around me. Not only is this an otherworldy experience, it also is a good indicator of how healthy the ecosystems are. If you are in Slovenia, I can’t recommend enough taking at least one evening to walk alongside a lake or river to experience this.

Wildlife aside, the people were also among the friendliest I have encountered. Especially at weekends, you would regularly be greeted by cheerful locals enjoying the trails. And multiple times after simply asking for directions, people would take an interest in what I was up to and invite me in, offering water, a cool beer or even some homemade pastries.

In fact, as a young, solo female hiker, I don’t think I have ever felt safer in any country. Hard to pinpoint why exactly, but the female travellers reading this will relate when I say you just learn to ‘read the air’ in a place. So I was more than happy to spend hours out on the trails enjoying some headspace and unspoilt nature.

And this is how I ended up scrambling down Stol in a flash storm.

Should I take cover under a tree and wait to see if it will pass? I thought. No, there’s too much lightning overhead to want to be under trees this far up and it’s going to be dark in a few hours (no long northern European summer nights here).

There wasn’t anywhere to stop anyway, the path just kept winding steeply down, zigzagging left and right apparently whenever it felt fit.

Suddenly the cloud caught up with me. A dense, white fog swallowed up everything around me, an advancing front of claustrophobia taking no prisoners. My gage of how far I had to go was totally lost and I had to intently focus just to see where I was placing my feet.

Just keep going, inch by inch, until you get down, I told myself. That’s the only thing you can do right now. So that’s what I did, displaying a magnificent array of side steps, lunges and skids, painstakingly working my way down the mountain.

It’s funny how meditative situations like this can be. One moment you’re a tiny speck in awe of the vastness of the outdoors, the next you’re in your own microcosm, only seeing what’s five feet in front of you and listening to the endless monsoon of raindrops. It was like someone had put cotton wool over my eyes and ears. Sure, I had prepared all I could, brought all the equipment I could possibly need, had sought advice from locals before heading up, but still, the mountains still take you by surprise and teach you more.

And then, after spending nearly two hours like this (I checked later since at the time I had no idea how much time had passed in my descent), I popped out below the fog, like a cork out of a bottle of fine, Slovenian wine. A stunning alpine meadow lay before me, a scene that seemed to breathe out serenity in the same manner any back garden does after rain. A sweet, damp freshness filled the air.

The landscape was slowly crawling back to life; birds were beginning to sing again and insects started buzzing around me once more.

I instantly knew where I was; I had passed this meadow a short while into my ascent, and I was only a few hundred metres from the bottom. What gushed through me was not a sense of relief, but one of gratitude; that Stol had welcomed me up its slopes, granted me its summit, then gobbled me up, chewed and spat me back out in one piece again – and this time with a little more humility and experience.

I turned around and gazed back up at where I had come from. The tip of the peak was just emerging from the mist.

“Hvala, Stol” I shouted at the top of my lungs back up to the mountain.

“Thank you, Stol.”